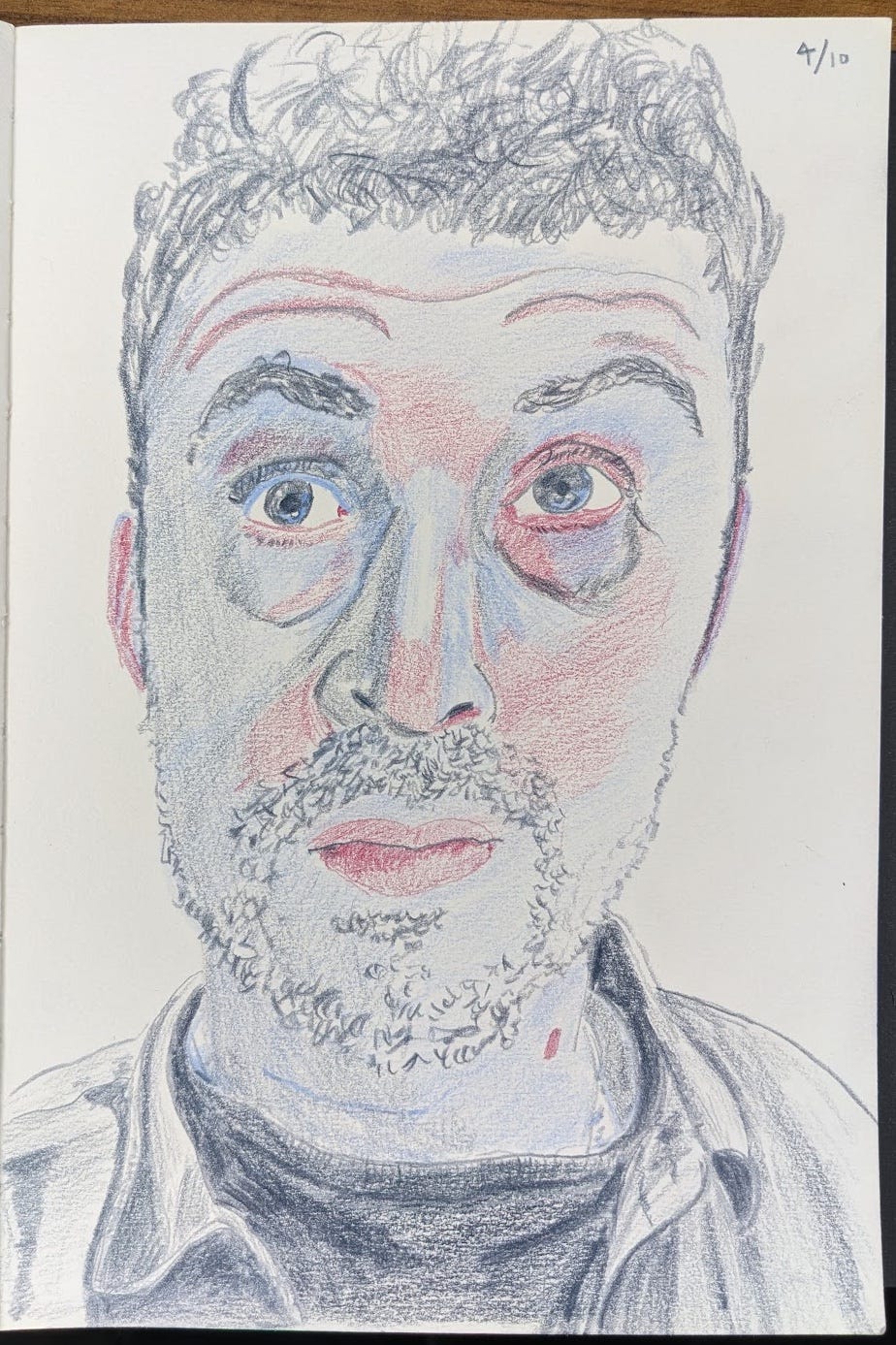

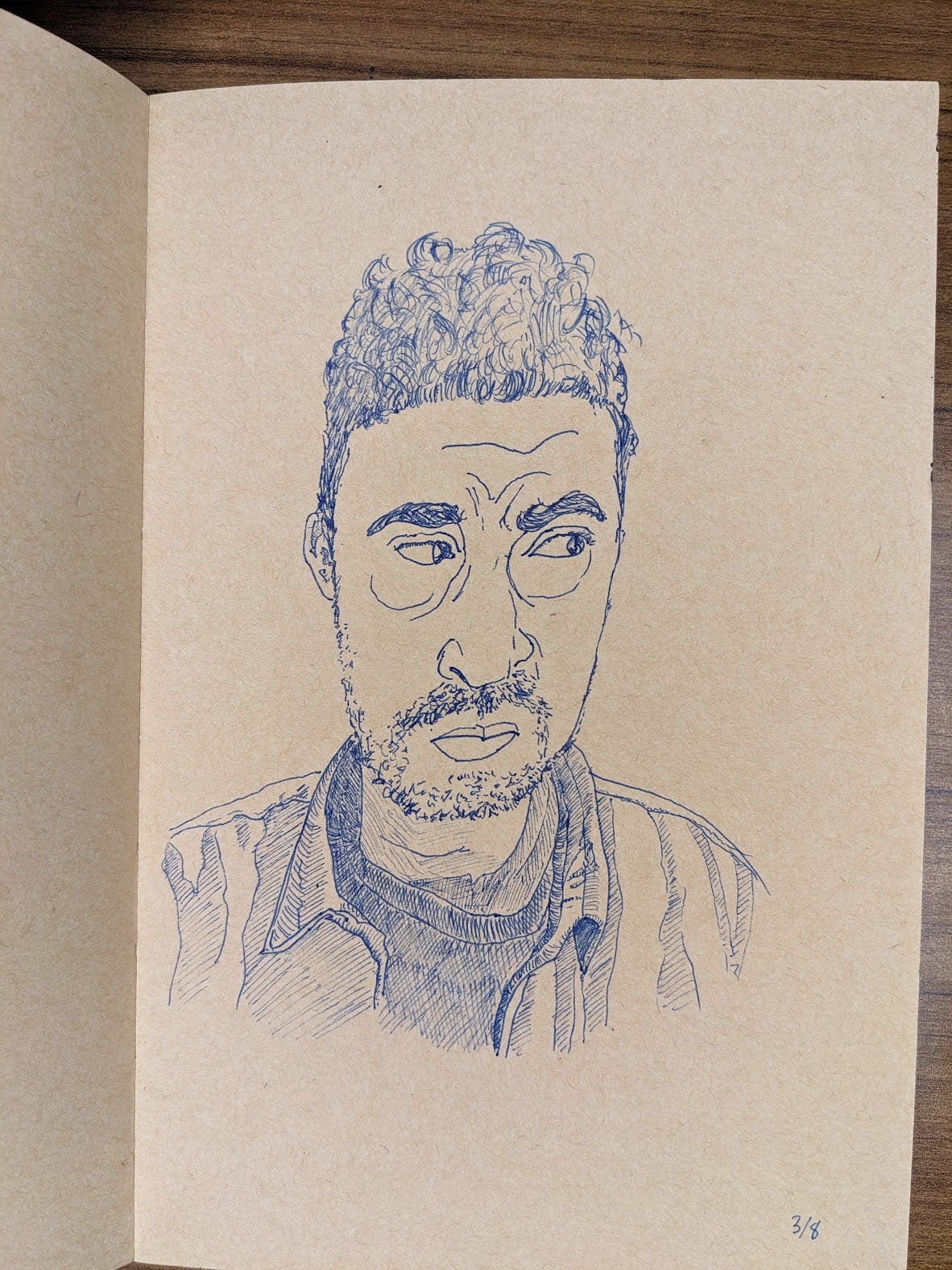

So I dropped my drawing classes at the community college, promising myself I would take responsibility for my own drawing practice (as recounted in the last letter). I admit I haven’t done a very good job of keeping that promise so far.

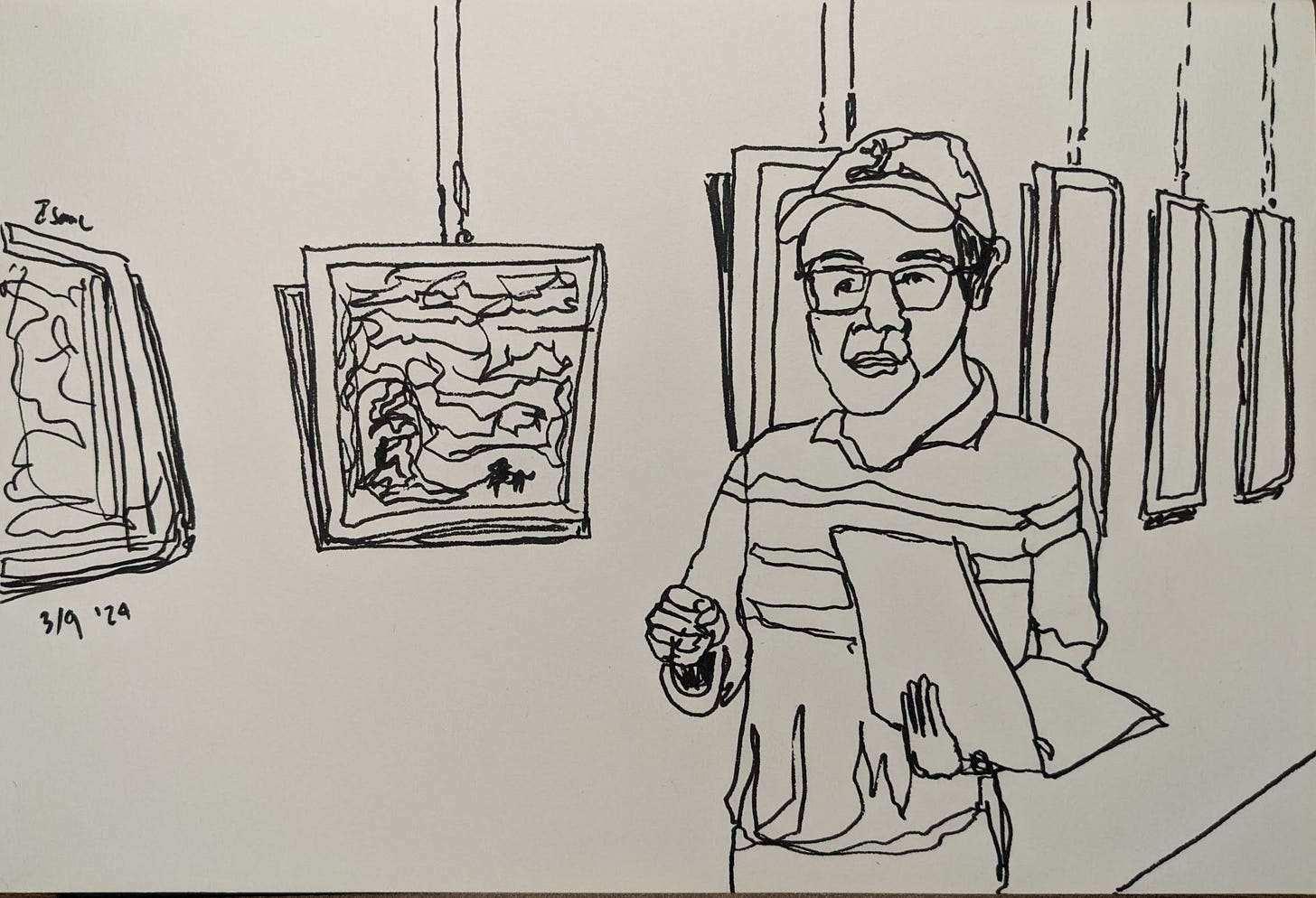

The same day that I dropped my classes, I visited Mr. Kuo’s watercolor exhibition. Mr. Kuo was there and gave us a tour. During the tour, he talked about how he became a professional artist.

Mr. Kuo once was a businessperson. He made a decent living and earned the respect of his peers — that is, until around eight years ago, when, amid an increasingly toxic work environment and workplace bullying, Mr. Kuo was let go. He lost his job, his self-esteem, and a big part of his identity.

To cut a long story short, it was rediscovering and rekindling his childhood love of painting that pulled Mr. Kuo out of the severe depression that came with joblessness, and that gave him a new sense of purpose.

For the next eight years, Mr. Kuo painted religiously, going on daily pilgrimages around the island on his scooter in search of vistas to paint, heedless of rain and scorching sun.

I needed to paint

I asked Mr. Kuo how he had supported himself during those eight years of artistic devotion. Had he just worked part-time jobs? Somehow it was hard to imagine Mr. Kuo’s serious, shy, and somewhat poignant demeanor donning a Starbucks apron and peering out from over a cash register.

Mr. Kuo shook his head. “There was no time to work. I needed to paint.”

Mr. Kuo responded cryptically to my raised eyebrows, saying he would send me a video later on.

The video turned out to be an interview he had done on a friend’s finance-themed podcast. In the video, Mr. Kuo describes how he was repeatedly saved from destitution by what seem like a series of fortunate, timely accidents.

There were many months between the time when Mr. Kuo lost his job, fell into depression, blew his savings on an ill-fated tea shop venture, and finally rediscovered his love for painting. In that time, his bank account had been drained to almost nothing. Just when he was despairing about paying the next month’s rent, he received a call from a former colleague whom he hadn’t seen since his termination.

Mr. Kuo visited the colleague at his office and showed him the painting he had just completed: the fruit of two sleepless nights, his first work since childhood, and evidently already something of a tour de force. The colleague commissioned five more paintings in a similar style, paying for all of it up front.

Beyond commissioned paintings, Mr. Kuo also made ends meet with income from postcards, which he marketed by cold-calling dozens of hotels and souvenir shops.

When asked by his friend if he has any regrets or concerns, Mr. Kuo responds: “I’m far from financially secure, but at least I know who I am.”

Magical thinking

This story reminds me of an idea that I first read about in the Julia Cameron’s classic The Artist’s Way, that when we take risks for the sake of something creative, we are usually rewarded in some way. “Take one step, and the universe takes three steps to meet you.” Also: “Leap, and the net will appear.”

It sounds like magical thinking, and it’s natural to approach such an idea with skepticism. But I now believe that it ultimately doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about something “real” or just imagined. Voodoo or confirmation bias, the effect is the same: what’s interesting about a belief like this is that it is, to a certain extent, self-fulfilling. Good things can only happen when we make room for them.

(I also believe that if we are really honest in acknowledging all the ways in which we deceive ourselves and all the self-limiting beliefs that help to keep us tethered to a recognizable identity — more than any one of us will probably ever discover in a mere lifetime — we might also be more humble about deciding what can and can’t constitute our own reality.)

Predictably, listening to Mr. Kuo’s story and hearing about his courageous perseverance in his creative pursuits made me feel more than a little sheepish about where I’ve hesitated, and how much I fret about things like achievement, legitimacy, and financial security.

To exculpate myself, I dashed off an impassioned rant on Facebook about how we should all take more creative risks and worry less about practical concerns. The gist of it was that, since we’ve already come this far and the universe hasn’t yet rained plagues down on us (“plagues” in this case referring to any mechanism, indifferent or otherwise, that can snuff out life or make doing art impractical, including: disease, violence, insanity, imbalance, accident, asteroid, the atmosphere evaporating, and also never having been born in the first place), maybe it would behoove us to come out of our shells a little more and take bigger creative risks. Unless, of course, one actually is being visited on by plagues, which of course do happen and do affect millions and millions of lives (not to mention the infinity of possible humans who are never born in the first place), in which case, you can take my argument with a grain of salt.

I ended by thanking Mr. Kuo for the inspiration, and clicked on “post.”

As happens more often than I’d like to admit, I was jolted awake in the middle of the night by the realization that I was terrible human scum for writing what I had written. How dare I efface people’s phones and laptop screens with such callous and entitled mumbo jumbo?

What about all those people — some of my friends among them — who are trying as hard as they can to build a career as an actor or an artist of some kind, and for whom working a part-time job is a necessary price to pay for the freedom to follow their passion? Who was I to recommend they throw caution out the window — or to leap out the window themselves, never mind, and expect that “the net will appear”?

In that moment I was fully aware of all the nets that had already been set up to catch me, should my own half-hearted, guilt-ridden show of bravado fail. How could I pretend to understand in the slightest what it’s like to be someone else?

I flung open my laptop and archived the post. Then I got back in bed and shut my eyes tight, despairing at ever being able to write another truthful line of text again.

What’s an art career?

After I visited his exhibition, Mr. Kuo sent me a message. He suggested I rethink dropping his class. Even if I was busy, he said, the relationships I was building with my classmates might turn out to be important for my career. He even generously offered to let my partner Lori stand in for me on days when I couldn’t go (she had done that a couple times last semester, when I was the class monitor and my absence meant there would be no attendance sheet).

This brought up some questions for me. Was I planning to have an “art career?” If so, what did that even mean?

I’ve asked myself, and also been asked, if I wished to have my drawings shown in a gallery of some kind. Traditionally, my answer has been no. Yes, I suffer from imposter syndrome. I also seem to believe that I haven’t “put in my time” yet. But maybe the biggest reason is that the idea simply terrifies me.

Of course, I’ve also been to plenty of art shows where the work was terrible, commercial, and/or trivial, and I found myself thinking “I could do better than that” (this couldn’t possibly just be my own insecurity trying to protect me by being judgmental of others, not a chance!). At times I have even thought that the only real difference between accomplished artists and novices is that the former use much bigger canvases.

In any case, Mr. Kuo’s argument about building relationships for some nebulous art career didn’t carry much weight with me, and I decided it was more important that I trust my own judgment.

So… why did I go to Mr. Kuo’s class this week?

A few days after I went to Mr. Kuo’s exhibition, Lori also went to see it. She came home that evening to tell me that she’d signed up for his class. “He says you can go in my place whenever I can’t make it.”

Great!

Defying convention

We met at Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall. I arrived late, partly from leaving the apartment too late, and partly because the map Mr. Kuo provided had south facing up, and I had stupidly assumed it was north.

Speed-walking through the park, I berated myself for not reading the map more carefully, for not waking up earlier, and for not being a better human being overall. Then I berated myself for being so hard on myself.

When I arrived, Mr. Kuo arm-punched me and smiled.

“Are you painting today?” he asked. “Better hurry up.”

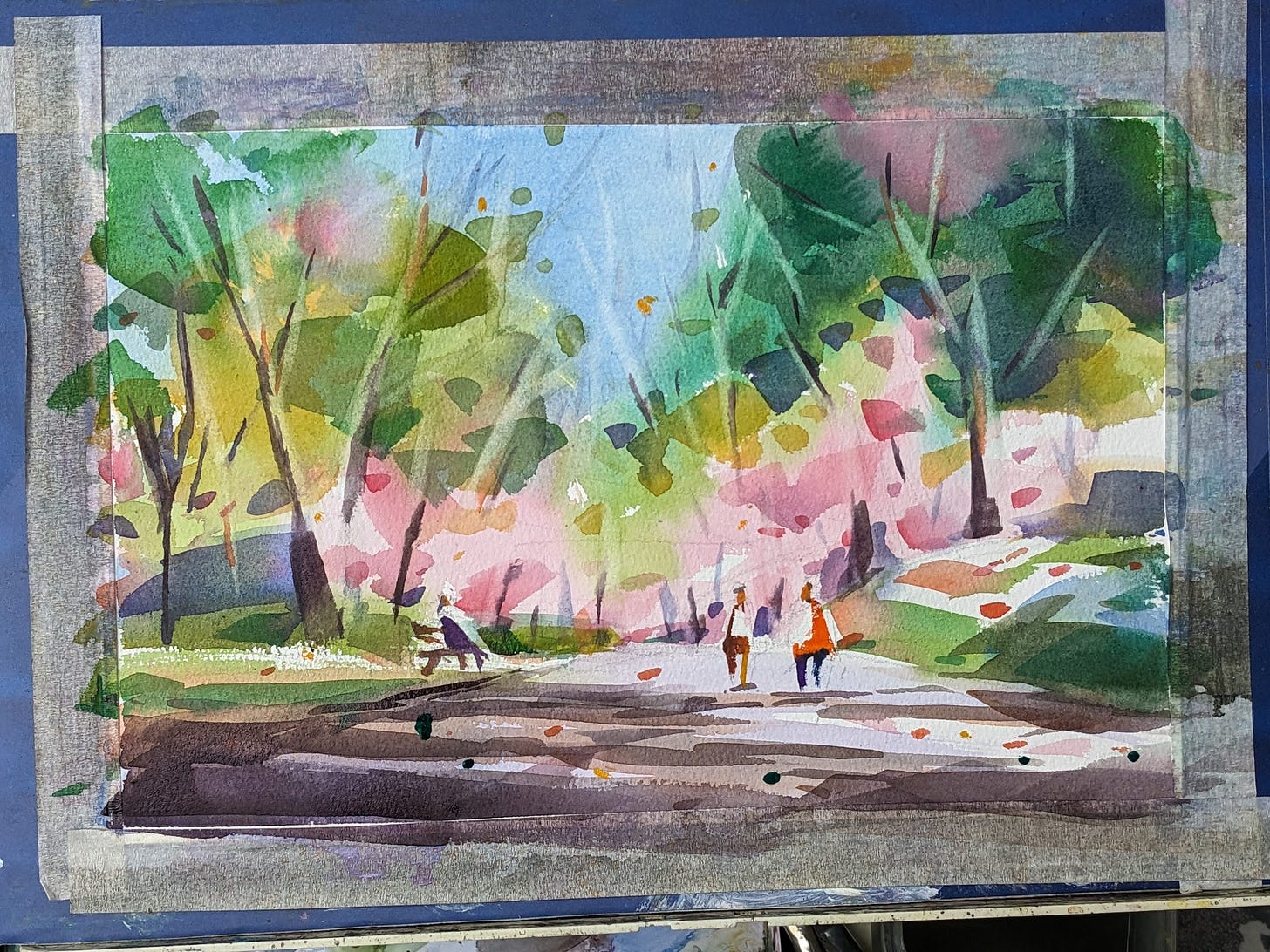

Mr. Kuo was demonstrating a semi-abstract painting style, with large, medium, and small blocks of color that somehow, as if by magic, morphed at a certain distance into trees, rocks, leaves, and cherry blossoms. Even more miraculously, these layers of triangles, trapezoids and rhombuses of color created the illusion of depth.

Sitting down to draw, I could feel some part of me rebelling against the idea of copying the master. It seemed pointless. Too far beyond my capabilities. Instead of painstakingly trying to mimic his every brushstroke, I decide to try and break free.

The results were disappointing. I tried again, this time thinking I would take a more focused approach by only practicing one of the many skills that Mr. Kuo was demonstrating instead of trying to do it all at once. In this case, I tried copying his brush strokes, using solid shapes of various sizes. Mr. Kuo had repeatedly emphasized the importance of having a combination of large, medium, and small shapes.

Even this turned out to be much harder than it appeared. I was so used to giving my hands free rein, letting them trace their own halting, spasmodic path across the page. It was more than awkward trying to rein them in now, forcing them to make careful, controlled marks without jagged edges.

My inner artistic child at this point started throwing a fit.

“I’ll never be good at painting! This is too hard! It looks like shit! What am I doing? At least the other students have something to show for their trouble — a recognizable landscape painting, even if an inferior copy. Me? I have nothing!”

As I drowned in my own self-pity and shame, I tried telling myself it didn’t matter. The point wasn’t the product; it was the process. What I was doing was trying to let go of the need to always make a finished product that looked nice, to let go of the pressure and anxiety that such a need creates. I was trying to set myself free.

The self-pity didn’t just evaporate, but I could tell that the little artist boy was listening. I had his attention. Now, what to do with it?

I kept painting. I put more colors on top of the other colors. The colors turned muddy and dark. I brushed them off with water and started again. I saturated the paper with turbid pigments. I did everything I wasn’t supposed to do. I tried to have fun.

While we had been painting, Mr. Kuo had been making the rounds. Occasionally he would stop behind me and watch in silence. This time, however, seeing that I had completely lost my mind, Mr. Kuo let out an involuntary exclamation of dismay.

“Ai-ya!”

I looked up and shrugged. Even as some tiny part of my rejoiced at this newfound freedom, most of me was still feeling despondent. I wanted someone with authority like Mr. Kuo to tell me everything was going to be alright; to hold my hand and show me how to paint. I didn’t want him to say “Ai-ya!” and shake his head at me.

When class was over, I wandered out of the park and onto the street in a daze, feeling like an outcast and a fool for the duffel bag full of paper and brushes on my shoulder. What was I doing with all that stuff, when clearly I couldn’t paint for beans? Who was I fooling?